When a group of Sydney high school students replicated the active ingredient in price-hike drug Daraprim for a fraction of the cost the story, and Martin Shkreli's reaction to the news, went viral. As well as being a great illustration of how educators can involve students in real-world research, it's also a tale of resilience and perseverance.

‘We've got it.' It was the confirmation Sydney Grammar School science teachers Dr Erin Sheridan and Dr Malcolm Binns and eight Year 11 students had been waiting almost a year for.

Recounting the story to Teacher magazine, Binns says they'd handed their final Daraprim material of 2016 in to University of Sydney researchers to be processed as part of the Breaking good – Open Source Malaria Schools and Undergraduate Program.

‘I'd dropped it off at the university (on the Thursday) and I had heard nothing. I was thinking “I wonder if nothing's worked?”. About 10.30pm on the Saturday Dr Alice Williamson, who is our contact there, sent me an email with big, bold letters: “We've got it. Hurray!”.

‘She was thrilled and there were really two aspects of that. One was her excitement, the bold letters in the email, but also that she's involved in other projects and things and 10.30 on the Saturday was the first chance that she had to run the spectra. But she did, she was in there at that time on a Saturday night, and it was just wonderful being part of that.'

Back at school, Binns could not contain his excitement. ‘When I mentioned it to the boys the next day, they actually tell me it was one of the highlights of the whole time. I was out in the playground and they could see me coming with this great big grin on my face.'

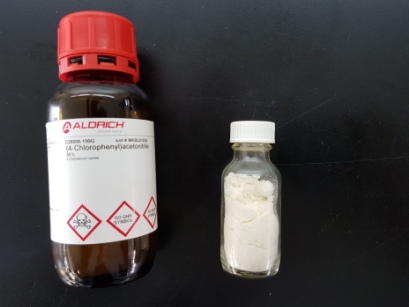

The team had every reason to be elated. They'd finally managed to make pyrimethamine, the active ingredient in Daraprim. The drug hit the headlines in 2015 when Martin Shkreli, CEO of Turing Pharmaceuticals, increased the cost overnight from US$13.50 to $750 per dose. The students had produced 3.7 grams at a cost of US$20 (a similar quantity in the US has a value of US$110 000).

[Students started with inexpensive chemicals and made the sample of Daraprim, pictured right, which has a market value of AUD $150 000. Image: University of Sydney.]

Contrary to the initial reaction of Shkreli on social media – he played down the achievements of the students arguing ‘learning synthesis isn't innovation' and ‘almost any drug can be made at small scale for a low price' – this was a tale of resilience and persistence.

Trial and error

‘I'm looking after this [Daraprim] project for Dr Sheridan while she is away on maternity leave,' Binns explains. ‘We've been doing similar sorts of things with the University of Sydney now for about the last two years. We love it because it's an opportunity for the boys to get hands-on skills. This is Chemistry, in particular (and mainly with Year 11s). We're fortunate that both Dr Sheridan and myself are organic chemists – that's what our degrees are in – and we've got laboratory skills.'

The students worked on recreating the drug outside of normal lessons, attending three sessions a week either in a morning, 7.30-8.30am, at lunch or after school from 3.15-4.30pm. Binns says he thought it would take a term – in the end, it took three terms and lots of trial and error.

‘The students are working from an almost zero knowledge base and they're basically skilling up. For someone in the pharmaceutical industry who's been there for 10 years or so, it would be a completely different story, I suspect.

‘It does take a long time for things to happen – in the early days, something which might take an experienced person 10 minutes will take 40 minutes and that's because everything's unfamiliar and the boys want to make sure they're doing things right. And, as a teacher you want to make sure that they're safe when they're doing it so you're particularly careful – you're always careful. As they develop the skills and develop them safely … they become more confident with the equipment and chemicals and you do move a bit faster, but at first the initial stages are very slow.'

Binns says the students came to an appreciation that the reaction itself may take a day, but you can spend the next week working on extracting the compound you want. Safety, the educator reiterates, is the number one priority. He explains the common industrial way to make the compound uses toxic materials that are gases and carcinogenic – materials that would never be seen on a school site. ‘We have no plan to use that so we looked around at alternative ways. It may not be the most efficient from an industrial scale, but we're doing it as “what's the best way that we can do it from a school person's way?”.

After two months the group stopped trying and took a step back, thinking ‘no, it's just not going to work'. The students did a literature search and spoke to the university experts, and the teachers offered their suggestions. ‘It's very much a group thing; it's good for the boys to see that science these days is not really the work of an individual but you need to be working as part of a group.

‘There are times they get quite depressed … the same for me too, you know, nothing's working. But then you get the moment where something works.'

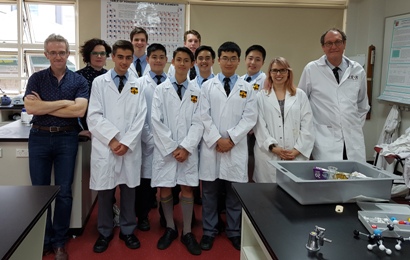

[From left to right: University of Sydney researchers Associate Professor Matthew Todd and Dr Alice Williamson, the Sydney Grammar School students involved in the project and their teachers Dr Erin Sheridan and Dr Malcolm Binns. Image: University of Sydney.]

Applying skills and knowledge

One of the students involved in the project, Austin Zhang, told reporters that working on a real-world problem upped the enthusiasm levels. Binns says the open source project is a great way to introduce students to new skills, equipment and processes. However, he adds a lot can be achieved through simple chemistry.

‘We did column chromatography, where you put a silica column and run the material down. We talk about chromatography in First Form, it's part of our course where you put coloured pens on filter paper and you let the water run up and you can get the different colours.

‘It's a wonderful First Form or primary school experiment and they use a more sophisticated version when they're in Year 12. So, it's really good that they can see something which they've learnt in their earlier years and see firsthand the application to industrial production.'

Advice for fellow educators

His advice for other schools looking to get involved in similar projects? Binns returns to the topic of safety. ‘You need to have people that are supervisors at the school who have sufficient safety skills in the area. … The university people aren't there all the time [but] your teacher is.'

The school has fume cupboards, allowing students to carry out reactions using solvents without breathing in the fumes. ‘Many chemicals that are potentially dangerous, if they're handled well they're quite safe. For example, one of the materials we use is potentially caustic but we use the whole bottle – we put the whole bottle in, so we don't have to weigh it out, there's no handling.'

Cost is also a big consideration. Getting involved in the Open Source Malaria project meant they could send their samples to the university to be analysed using Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) technology – expensive machines that would otherwise have been out of their reach. However, although it was considerably cheaper to make Daraprim than to buy it in the US Binns says schools still need to factor in the cost of things like stirrers, glassware and the chemical materials.

In what ways do you provide students with opportunities to apply what they're learning in class to real world issues?

How can your school develop partnerships with local industries and educational institutions?

Dr Malcolm Binns says safety should be the number one priority for science educators. What safety procedures do you have in place at a school and classroom level?