You and your students may have access to lots of technology in your classroom, but are you making the most of it? The Digital Pedagogies Lighthouse Project at St Joseph’s Catholic Primary School in Queensland has seen staff work with a specialist Education Officer to make the shift from using tech tools for productivity and presentations to embedding them in authentic mathematics learning. Here, Vanessa Crouch (Toowoomba Catholic Schools Education Officer: eLearning), and teachers Renee Richardson and Melissa Ferguson, share what’s happened so far and where to next.

For three years our teachers have been working to increase their knowledge and skills in digital pedagogy.

With a one-to-one program rolling up from Prep, our school recognised that we were not leveraging the digital tools we had in our classrooms for learning as effectively as we wanted. The authentic use of technology was mostly limited to publishing, presentation or drill and practice.

Enter the Digital Pedagogies Lighthouse Project. This is a project based on the London Challenge (Kidson & Norris, 2014; Woods & Brighouse, 2014), instructional coaching (Knight, 2010 & 2016; Knight & van Nieuwerburgh, 2012) and action research (Bradbury-Huang, 2015; McAteer, 2014; Nasongkhla & Sujiva, 2015). It has been supported by the Diocese of Toowoomba Catholic Schools Office and an Education Officer who specialises in digital pedagogy and digital learning.

We chose the Technological, Pedagogical and Content Knowledge (TPACK) framework (Baran et al., 2019; Voithofer et al., 2019) as the theoretical framework used to begin developing our professional knowledge. It underpins a variety of educational technology research today (Koehler et al., 2013; Mishra & Koehler, 2009; Shin et al., 2009). The aim of this framework is to build the three knowledges equally so that teachers are able to make decisions about how to best develop learning experiences that incorporate technology in authentic ways.

Where did we start?

We began with teacher professional learning, which took about a year. Using the research related to TPACK (see above) and digital pedagogy (Tabesh, 2018), teachers began increasing their knowledge and skills with a small suite of digital tools – such as BookCreator and the Math Learning Center apps – as well as consolidating their content knowledge in mathematics. We felt mathematics was an area of the curriculum that needed some refreshing at our school and decided to focus on the development of our digital pedagogy skills in this area. We also began a process of instructional coaching.

Our Education Officer provided in-class modelling of how to use digital tools in our classroom, and this was followed up with teacher time to practise using the tools and discuss effectiveness and impact. This modelling allowed us, as teachers, to become more proficient users of the tools and it built our confidence to experiment more with them. As a staff, we shared our progress in our Professional Learning Communities, which gave others the opportunity to see what we were trialling in our classrooms. This professional sharing allowed us to ask questions, see connections and build our understanding of how we might use these tools in our own contexts.

During the project we collected data from teachers, parents and students. The teachers and parents completed surveys that delved into how they used technology, as well as their confidence and proficiency. For the students, we asked them to draw a picture of what learning looked like in their classrooms. Over the three years of the project, we saw a marked shift from a focus on digital tools for productivity or drill and practice to collaborative and communication tools that helped students share learning.

As we planned learning, we chose digital tools that would give students opportunities to demonstrate their learning and explore mathematical topics. Our choices depended on the required learning – for example, we might use video and photos with BookCreator, Keynote/Powerpoint to gather evidence of learning, or the Math Learning Center apps to demonstrate learning. This process was aided by using the Triple E Framework (Kolb, 2017) to help us determine the value of using different technology tools in our context.

What have we seen change?

Our teachers have reflected on their changes in practice regularly and, as a result, our school has developed a stronger culture of professional learning. Where teachers were once scared to ask and unsure of how to use an app or embed technology authentically, we now collaborate and share with great enthusiasm. The development of this collective efficacy, combined with a clear understanding of what digital pedagogy is, has enabled us to create authentic and valuable learning experiences for our students.

In addition, teachers know where to look or who to talk to when interested in embedding new technologies in their pedagogy. We appreciate that all staff have strengths and weaknesses in regards to technology use, however, there is always someone who can give guidance on how to improve or introduce a new tool which could be useful for the area of curriculum being focused on. As we encourage our students to have a growth mindset, have a go and learn from their mistakes, we know it is imperative that we, as teachers, must model these values ourselves.

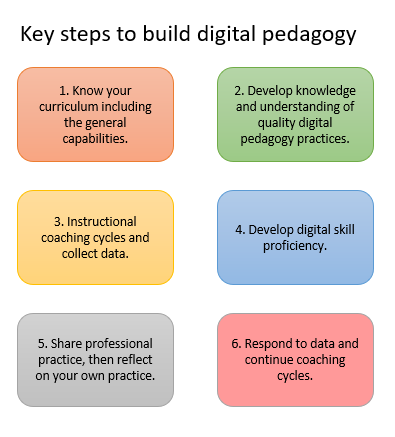

Figure 1. Our key steps to build digital pedagogy

Our teachers are now critical users of technology. Once we would have obliviously used drill and practice apps or a website that vaguely related to a topic and believed that to be ‘embedding technology’. Now we have developed a critical lens to judge the value or ineffectiveness of certain technologies, we are able to make better decisions for learning. We see the value in using technology as an authentic tool for teaching, learning or assessment, rather than it replacing a paper-based resource. There is no educational value in using every app, website or piece of hardware available. We have learnt to choose a small number of resources, teach students to use them well and use them across subjects.

Our students have become more confident creators of digital content, transferring their knowledge learnt from the digital tools used in mathematics to other key learning areas. They show an ability to effectively choose a tool to assist them to demonstrate their knowledge and understanding. Student language and ideas around what technologies they use in their learning has changed. At the beginning of the project, students related technology to only being ‘fun’, they now relate technology to the tools and skills they can use to enhance and share their learning.

Our use of digital tools to differentiate has also been invaluable. For example, using tools such as BookCreator and Keynote has supported students in achieving individual success, whilst also taking away some of the academic pressures (ability to read and write). We’ve used the audio and video recording in these tools to enable students to share their learning in a variety of ways, rather than just as a written piece of work.

The way assessment is completed has also been transformed. Students are now confidently able to display knowledge in a variety of modes, including video, voice-over and graphic annotations. Therefore, the way teachers assess and give feedback has changed. No longer do we take home a collection of paperwork or pile of students’ books for every subject during assessment time. Assessment for a subject or topic can be sent to the teacher’s iPad or laptop for marking and feedback. Additionally, online student collaboration has been explored in the upper primary grades. Peer feedback is given through comments on the digital document and collaboration on tasks has been simplified. The possibilities have been endless.

Our teachers now have greater clarity of the curriculum, deeper purposes for using technology and are critical reflectors on their practice. Our students are now more capable technical problem-solvers and proficient users of digital tools.

Where to next?

The progress we’ve made over the last three years is just the beginning. Next steps for our school include:

- Expanding our digital pedagogies learning into all curriculum areas;

- Adding a few more digital tools to our repertoire;

- Moving towards the teachers being the modellers of practice;

- Refining our planning processes to ensure that digital tools are effectively utilised;

- Sharing our learning with other schools and teachers;

- Reflecting on the data from our project to ensure that we can sustain the momentum in what we are doing to enhance student learning.

References

Baran, E., Canbazoglu Bilici, S., Albayrak Sari, A., & Tondeur, J. (2019). Investigating the impact of teacher education strategies on preservice teachers' TPACK. British Journal of Educational Technology, 50(1), 357-370. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12565

Bradbury-Huang, H. (2015). The SAGE handbook of action research. SAGE.

Kidson, M., & Norris, E. (2014). Implementing the London Challenge. Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Knight, J. (2010). Unmistakable impact: A partnership approach to dramatically improving instruction. SAGE.

Knight, J. (2016). Better conversations: Coaching ourselves and each other to be more credible, caring, and connected. Corwin.

Knight, J., & van Nieuwerburgh, C. (2012). Instructional coaching: A focus on practice. Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice, 5(2), 100-112.

https://doi.org/10.1080/175218...

Koehler, M., Mishra, P., & Cain, W. (2013). What is technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK)?. Journal of Education, 193(3), 13-19. https://doi.org/10.1177/002205...

Kolb, L. (2017). Learning first, technology second: The educator’s guide to designing authentic lessons. International Society for Technology in Education.

McAteer, M. (2014). Action Research in Education. SAGE.

Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. (2009). Too cool for school? No way! Using the TPACK framework: You can have your hot tools and teach with them, too. Learning & Leading with Technology, 36(7), 14-18.

Nasongkhla, J., & Sujiva, S. (2015). Teacher Competency Development: Teaching with Tablet Technology through Classroom Innovative Action Research (CIAR) Coaching Process. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 174, 992–999. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.723

Shin, T. S., Koehler, M. J., Mishra, P., Schmidt, D., Baran, E., & Thompson, A. (2009). Changing technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK) through course experiences. Proceedings of Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference, 4152–4159.

Tabesh, Y. (2018). Digital Pedagogy in Mathematical Learning. In G. Kaiser, H. Forgasz, M. Graven, A. Kuzniak, E. Simmt, & B. Xu (Eds.), Invited Lectures from the 13th International Congress on Mathematical Education (pp. 669–678). Springer International Publishing.

Voithofer, R., Nelson, M. J., Han, G., & Caines, A. (2019). Factors that influence TPACK adoption by teacher educators in the US. Educational Technology Research and Development, 67(6), 1427-1453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-019-09652-9

Woods, D., & Brighouse, T. (Eds.). (2014). The Story of the London Challenge. London Leadership Strategy.

Think about your own classroom practice: Are you making the most of the digital tools available? What criteria do you use to select the technology you use for learning activities?

As a school leader, do you give teachers time to practise using new tools and technology, and to discuss their effectiveness and impact with colleagues?