Setting high expectations, putting faces on the data and making student growth visible to the whole community has helped accelerate literacy learning at a Perth primary school.

At the start of 2013, six out of 10 K-6 students at Medina Primary School were reading and writing at a five-year-old level or not working at a grade level.

The school serves a low SES (socioeconomic status) area. Around 40 per cent of students are from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander background.

‘The school had been on quite a journey over the last five to 10 years where they'd really worked on the culture and the behaviour to create a quality learning environment. But, they were yet to make an impact on the student outcomes,' Sheri Evans recalls.

‘So, although they'd seen massive changes in the way the school looked, the way the students presented themselves and their behaviour in the classroom, they hadn't seen the kids academically, in reading, writing and numeracy, change their outcomes.

‘It was accepted that they may not learn and [so we] really needed to shift that. That was not okay and that the kids needed to and could learn, and it wasn't okay for us to accept that was the end of their education journey.'

At the time, Evans was Medina's Deputy Principal with Curriculum Leadership. She is now a Teaching and Learning Advocate at the WA Education Department's Institute for Professional Learning, sharing the successful strategies with remote and regional educators.

Evans says the approach at Medina was influenced, in particular, by the work of Lyn Sharrat and Michael Fullan (Putting Faces on the Data) and John Hattie (Visible Learning).

‘To us, it meant personalising the data and becoming really familiar with the students, but also making their learning visible to them. Because, it's quite an abstract concept that we walk into the classroom every day and talk about learning – but, what does that actually look like?

'One of my roles was to take the data that the school was already collecting but make that link between what was happening in the classroom and what we were seeing in the data.'

The school used a combination of strategies, supported by a comprehensive program of professional learning, classroom observation, team teaching, coaching and lesson demonstrations.

Challenging low expectations

Evans says the school looked to staff in the school who had previous experience of seeing students in low socioeconomic areas succeed to help challenge low expectations.

'We also used a whole heap of different messages from different people - getting our teachers out there, seeing what other schools were doing, listening to John Hattie's work, and ... proving that it could happen.'

To 'prove it could happen' at Medina, Evans and colleagues took a small group of students who were reading at five-year-old level and implemented a peer support program.

'[We started] showing that yes this could happen and therefore what you're saying about these children ... "we're doing the right thing but these children still aren't learning", we showed that wasn't true.

'Then that was a catalyst to get teachers to question their own beliefs.'

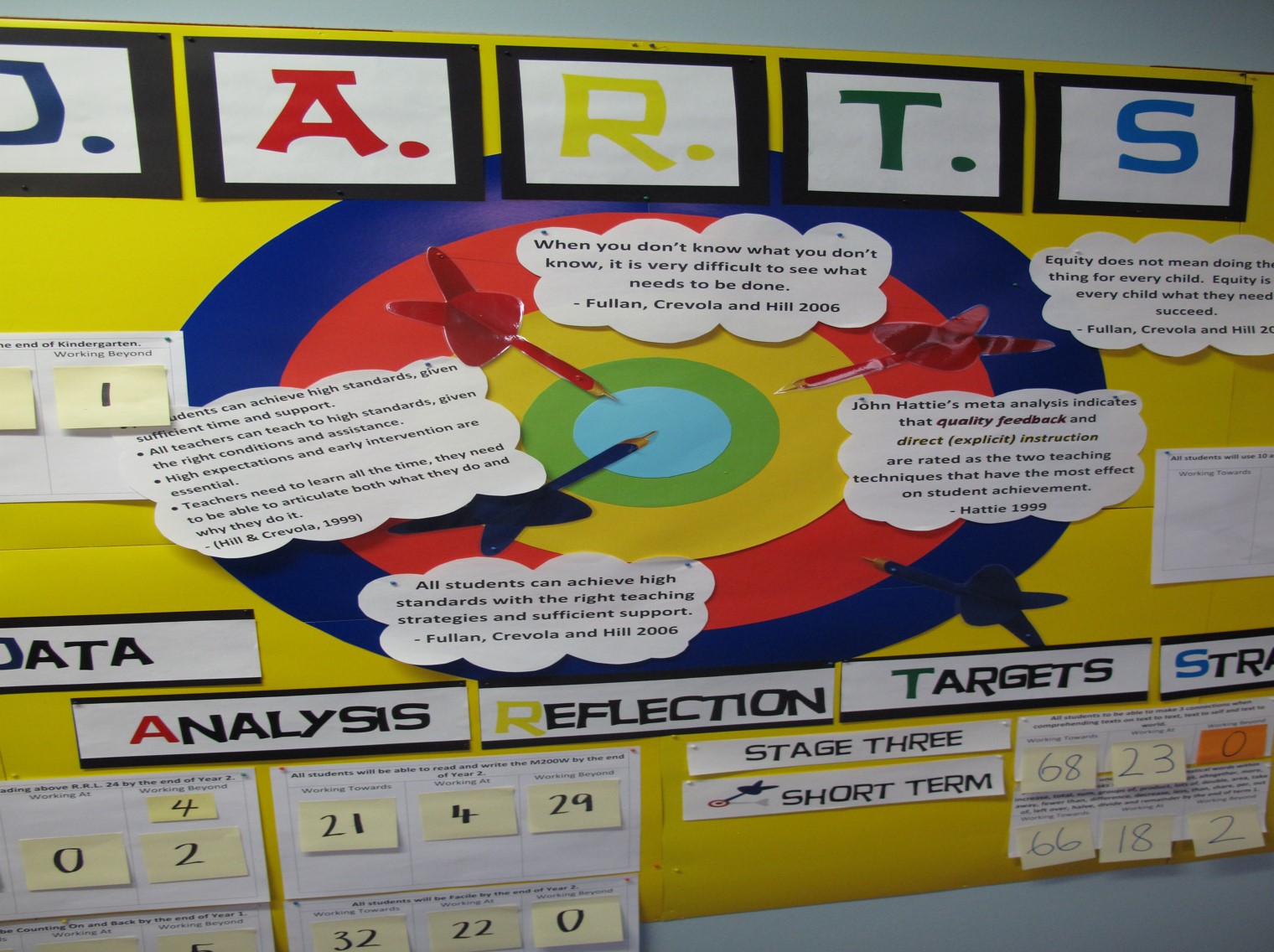

Big, bold data walls

An important plank of the multi-faceted approach was a school-wide focus on data, including making it visible. Printouts of small, complex spreadsheets were replaced with big, bold, colourful data walls.

'The aim was to de-privatise the data and help students to see their growth, but also help teachers to see growth and to see where students were at.

'We had data walls in all the common areas around the school - they were featured in the classrooms and they were data walls that were used by the students. We also had a data wall in the staffroom front and centre, where we had all our meetings.

'I think it was easy to ignore [it before]. There were some data walls, but they were really small and you had to go up really close and the information was quite complex.

‘I think another key was setting some targets. Previously, they were measuring their success by quite low expectations. Showing the data wall with [shorter-term targets] of where these kids needed to get to ... helped to open people's eyes I suppose, and make it more real, make it something that we couldn't ignore.'

Evans says the data walls worked well for 'constrained skills' that were easy to measure, such as phonics. For other skills, like writing and comprehension, they used 'bump it up' walls to give students ownership of their learning and make it visible.

Image: Sheri Evans.

'It gets students involved in the moderation process. They actually look at work samples and develop pointers that say "this work sample is 'x' because it's got this, this and this" ... and pointers to indicate what their next goals are and what they need to do to improve, for example, their writing.

'So it's really taking the moderation process away from the staff and teachers and giving ownership to the students, and knowledge to the students about what the next step is. That worked particularly well with our older students, who were looking at writing more complex samples and didn't know what the next step was.'

The impact

After nine months of the program student reading levels were measured. 'We found we'd made a significant difference to those 34 per cent [who were reading at a five-year-old level],' Evans says proudly. 'We'd halved that number.

'We also measured the whole school and saw that ... students were not only starting to read, but at a grade level and had accelerated two to three years in nine months. We didn't expect it to change students so much in nine months.

'We were aiming with the learning, the data walls, to really help students celebrate their growth and improve their self-esteem around learning. What we saw was this dramatic change to student behaviour - their willingness to be in the classroom, and their willingness to have a go.'

Evans says Medina Primary School has continued with the strategy and shares its work with schools in the local area. Her role now is to travel around WA and work with graduate teachers in a range of schools, particularly in remote areas.

'So, working with Aboriginal kids in those remote schools and sharing some of their strategies - sharing those data-driven targets and high expectation strategies with graduate teachers so we can make it more of a system-wide way of thinking, rather than just an isolated school.'

Sheri Evans was one of the Outstanding Presentation Award Winners at this year's EPPC (Excellence in Professional Practice Conference), where she shared Medina Primary School's story.

Do you and your colleagues know where individual students are in their learning?

Do students know what they are aiming for, and what their next steps are?

EPPC 2016 will be held in Melbourne on 19-20 May. The theme is Collaboration for school improvement. Call for submissions has opened - for more information about how to share your work with the education community at EPPC visit http://www.acer.edu.au/eppc or email eppc@acer.edu.au