Students who like to read – what does the research say?

What do Year 4 students think about reading? Is it fun? Do they think they learn anything? Sue Thomson explores these questions in her first Teacher column.

In 2015, a sample of students in Year 4 in Australian schools participated in PIRLS (Progress in International Reading Literacy Study). This was the second time Australian students participated in PIRLS and the results indicated that the average reading performance of Year 4 students had improved significantly since students were last tested in 2011. This contrasts with the results for 15-year-olds in PISA (Program for International Student Assessment), where scores for the average student in this older age group significantly declined over the past 15 years, particularly among higher-achieving students.

PIRLS focuses on Year 4 as the point in schooling where most students are moving from ‘learning to read' to ‘reading to learn'. However, reading is much more than a tool for education or work. It can take the reader out of themselves and their own experiences, engage and develop emotions and provide new perspectives.

As students move through this transition point, it is important to monitor not only their reading progress but also how they feel about reading – do they enjoy it? Do they think they learn from it? Do they read for fun? Students who answer ‘yes' to these questions are more likely to read more widely and gain greater skills, which in turn provides better scaffolding for further learning in all subjects and areas.

Student attitudes to reading

Positive attitudes and achievement are related and the influence runs in both directions: attitudes influence achievement and achievement reinforces (or perhaps alters) attitudes. PIRLS recognises the important role of student attitudes in reading achievement by collecting responses to two attitude scales – the Students Like Reading scale (a measure of participation and enjoyment of reading), and the Students' Confidence in Reading (a measure of their self-rated ability in reading). This article focuses on the Students Like Reading scale.

The Students Like Reading scale

The Students Like Reading scale summarises student responses to eight questions about how often they participate in and how much they enjoy reading. Students were asked to indicate their level of agreement (‘agree a lot'; ‘agree a little'; ‘disagree a little'; ‘disagree a lot') with each of the following eight statements:

- I like talking about what I read with other people.

- I would be happy if someone gave me a book as a present.

- I think reading is boring (reverse scored).

- I would like to have more time for reading.

- I enjoy reading.

- I learn a lot from reading.

- I like to read things that make me think.

- I like it when a book helps me imagine other worlds.

Students were also asked how often (‘every day or almost every day'; ‘once or twice a week'; ‘once or twice a month'; ‘never or almost never') they did the following activities outside of school time:

- I read for fun.

- I read to find out about things I want to learn.

Results

Students who very much like reading had a score that corresponded to them ‘agreeing a lot' with four of the eight statements and ‘agreeing a little' with the other four. They also reported that they read for fun and read things they chose themselves ‘every day or almost every day', on average. Students who do not like reading had scores that corresponded to ‘disagreeing a little' with four of the eight statements and ‘agreeing a little' with the other four. They also reported that they read for fun and read things they chose themselves only ‘once or twice a month', on average. All other students were assigned to the somewhat like reading category.

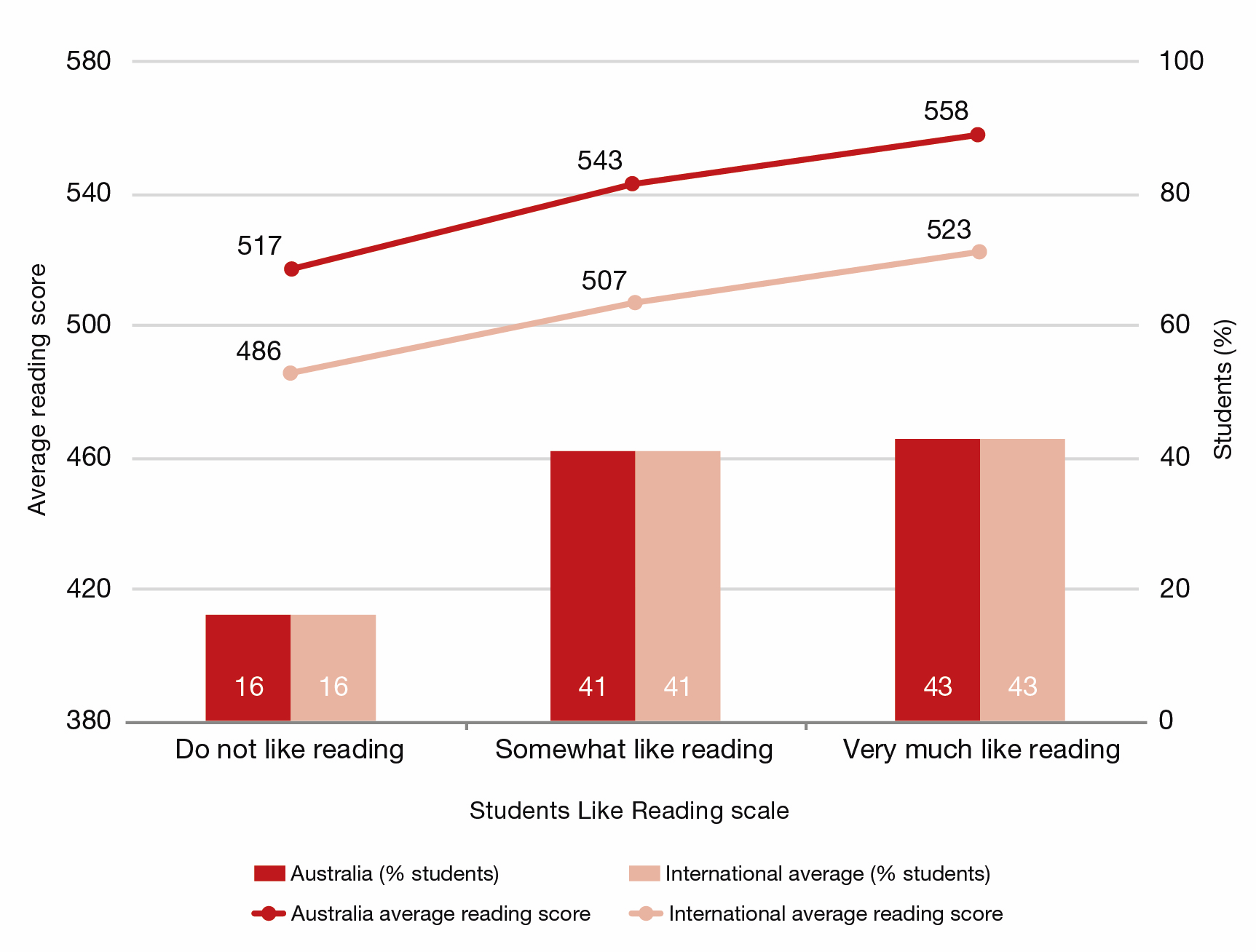

Figure 1: The Students Like Reading scale and Year 4 student achievement in reading, Australia and the International average.

Figure 1 shows that 43 per cent of Australian students very much like reading, 41 per cent somewhat like reading and 16 per cent do not like reading. This was similar, on average, to the distribution found across all participating countries. Some countries, such as Portugal and Kazakhstan, recorded higher proportions of students who very much like reading, while others, including countries who performed higher on average than Australia, had much lower proportions of students who very much like reading compared to Australia.

A general pattern could be seen in which students who very much like reading scored significantly higher in reading, on average, than did those who somewhat like reading, who in turn scored higher on average than students who do not like reading.

Gender differences

In most countries that participated in PIRLS 2016 (except for Macao SAR and Portugal), girls outperformed boys in reading literacy. In Australia, the difference was 22 score points: girls scored an average of 555 points and boys scored an average of 534 points.

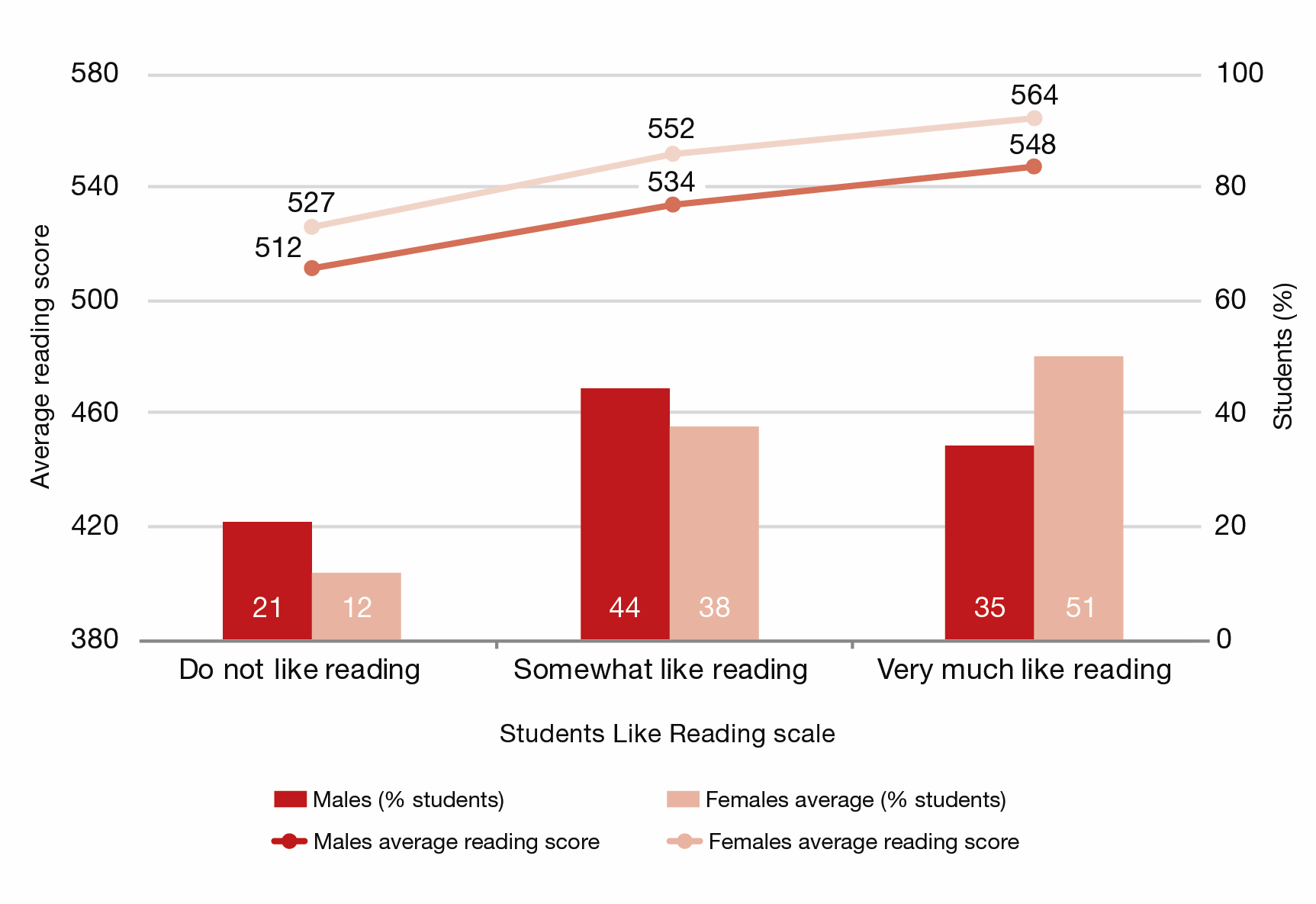

Figure 2 shows that the pattern of stronger reading performance by students who reported that they liked reading very much compared to their peers who like reading less, was also found among girls and boys. What is quite interesting, though, is the difference in the proportions of girls and boys at each level of enjoyment. Around one in 10 (12 per cent) girls compared to around one in five (21 per cent) boys responded to the items on the scale that indicated that they do not like reading.

Figure 2: The Students Like Reading scale and Year 4 student achievement in reading, by sex.

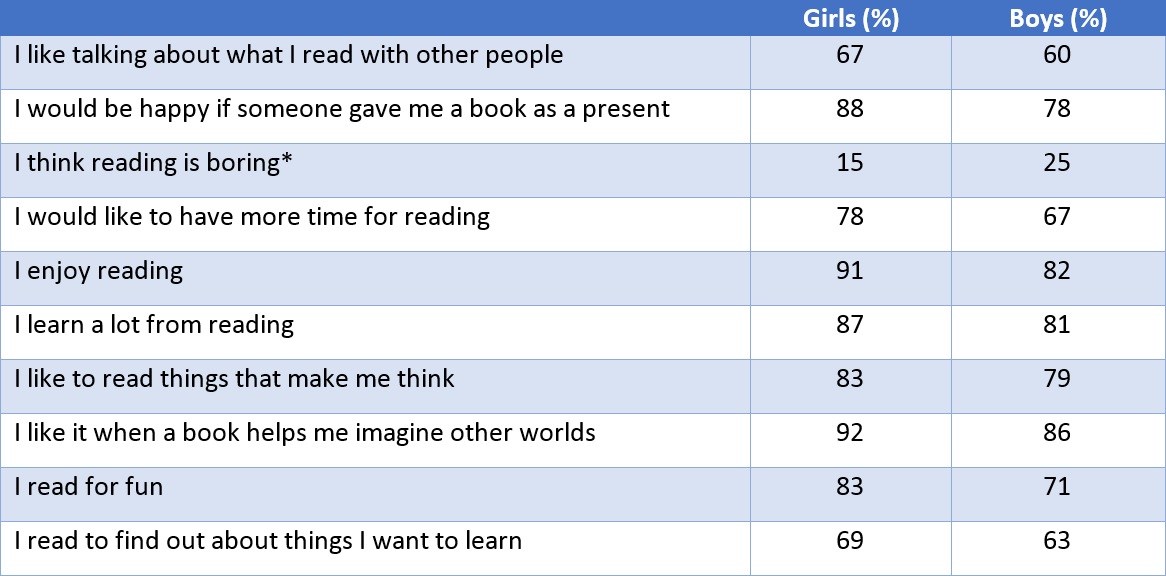

To unpack the gender differences further, each of the items that make up the scale are shown in Table 1, along with the percentages of girls and boys who agreed or strongly agreed with the item.

What do students think about reading?

Overall, the gender difference seen on the scale average, where girls scored higher than boys, is also present in each of the contributing items. However, there was some variation, with the differences being larger on some items, and relatively smaller on others.

The highest levels of agreement for both girls and boys were with items focused on getting a book as a gift, learning a lot from reading, and reading helping children imagine other worlds. Both boys and girls were more inclined to say that they read for fun (71 per cent and 83 per cent, respectively) rather than reading to learn (63 per cent and 69 per cent, respectively).

Table 1. Percentage of students responding ‘agree a lot' or ‘agree a little' to enjoyment of reading items

*This item is reverse scored when included in the scale. The percentages here reflect agreement with the item as it was presented to students.

Visit acer.org/snapshots to read about more about what we can learn from international studies.

With a colleague, brainstorm different strategies you employ to encourage students to read for enjoyment. What has proved successful in the past? Where could you go to find more support in this area?

PIRLS 2016 found that girls outperformed boys in reading literacy. Does this reflect what you see in your own classroom? Why do you think that such a substantial proportion of young students do not enjoy reading?