In their new book In Teachers We Trust: The Finnish Way to World-Class Schools, Pasi Sahlberg and Timothy D Walker suggest seven key principles for building a culture of trust in schools. They share examples of the Finnish school system in action, speak to practitioners on the ground about their work, provide questions for reflection for teachers and leaders, and offer up practical suggestions.

This exclusive extract for Teacher readers on the ‘three levels of trust’ is taken from a chapter discussing how educators can cultivate responsible learners.

The Three Levels of Trust

Mentor teacher Anni Loukomies told us about one of the major problems she sees in classrooms: ‘Many times . . . too much responsibility is offered to a student who has very poor self-regulation skills.’ In these instances, children often fool around. Alternatively, teachers who view some children as having undeveloped self-regulation may provide too little autonomy in the classroom. In this case, it’s easy for these students to become discouraged and bored. In both cases, their development can suffer.

Differentiated instruction serves as the best path to ensure that all children are moving forward. As we learned from Carol-Ann Tomlinson, professor of education at the University of Virginia, this approach is a respectful way of teaching. It optimizes instruction based on the children’s interests, preferences, and competencies.

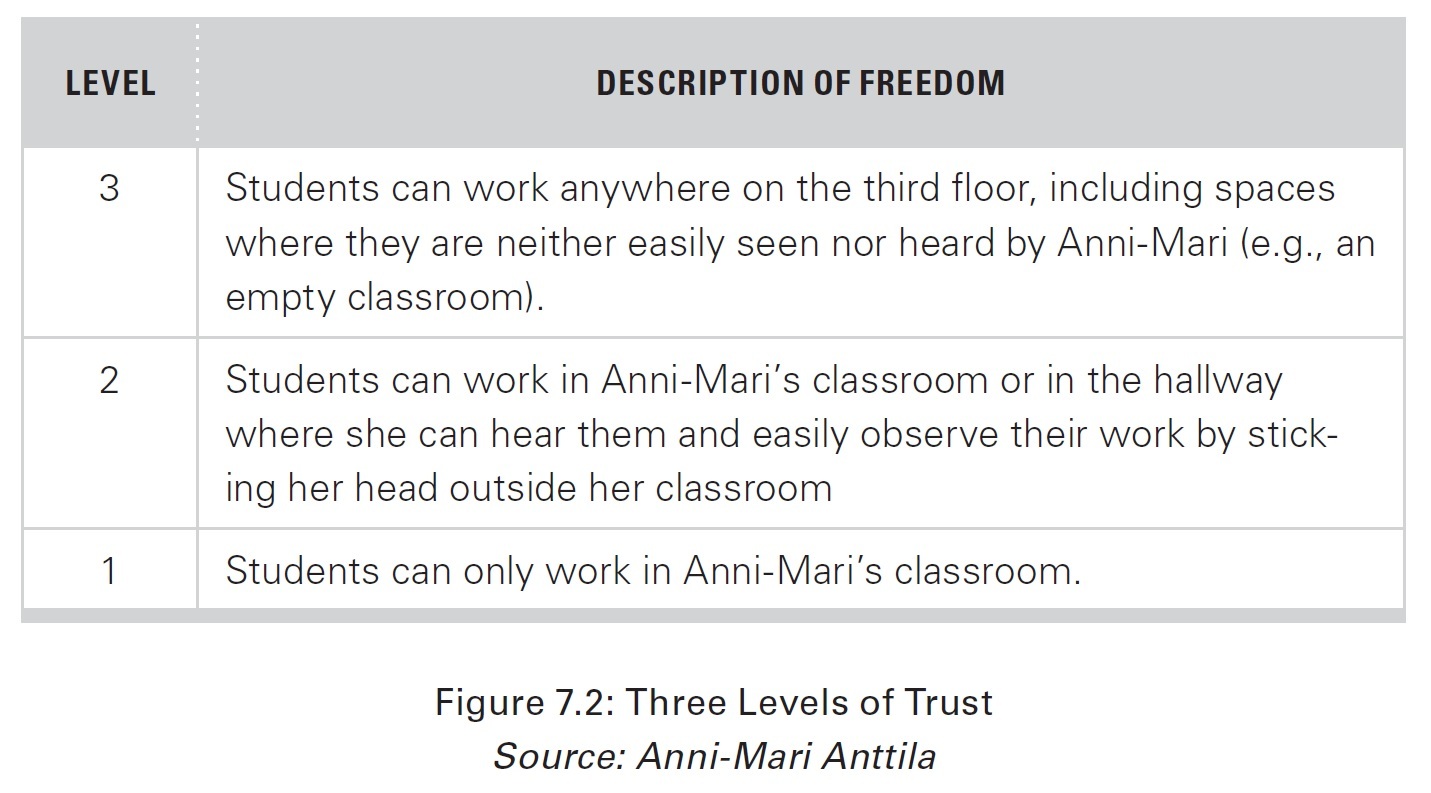

My Finnish colleague Anni-Mari Anttila at Espoo Christian School developed a differentiated framework for cultivating the autonomy of her grade 3-6 students. She calls it Three Levels of Trust, and this approach derived from her conviction that her students should be able to enjoy freedom, but only in proportion to their current levels of self-regulation. In particular, she evaluates their ability ‘to start, keep on task, not get distracted, [and] finish’ and, like Anni Loukomies, she lets this level dictate how much leeway she should offer them.

Anni-Mari’s third-floor English language classroom is inviting. Large exercise balls sit behind desks, and eight stationary bikes, positioned in front of large windows that let in plenty of natural light, stand in a semicircle in the back of the classroom. But when Anni-Mari gives her students the choice to work elsewhere, very few of them want to remain in her classroom. ‘They perceive it as great to be as far away from me [as possible],’ she said.

Anni-Mari knows that her students are highly motivated by autonomy. So she grants them choice about where they complete work in pairs. This decision to cultivate autonomy is where her Three Levels of Trust framework comes into play (Figure 7.2).

When she introduces this trust hierarchy in the beginning of the school year, every child starts at the highest level. She sets them up for success by ensuring that their first assignment – and every pair-work task for that matter – is something that they can easily complete on their own. Often the pairs will practice reading dialogue in English, taking turns as they read different lines, or they will play fun board games with dice. She emphasized that these are ‘activities that they know how to do.’ She added, ‘I know that they can succeed: They know what the expectations are; they know when they start; and they know when they finish.’

Anni-Mari explicitly teaches the expectations and procedure for pair work. Before allowing the children to leave her classroom, Anni-Mari draws names at random and requires that each child give a look of acceptance to their partner (‘no rolling of eyes’), establishing a tone of respect. She further described her routine, ‘They need to have their books open on the page that they are working on. They need to know what they’re going to do. Then they need to go settle down and come back when they’re done. . . .If I don’t see that happening . . . I need to go and get them back. Then they fall to the lower level of trust.’

Students who possess Anni-Mari’s highest level of trust enjoy visiting her old classroom, located on the other side of the third floor, that boasts a cozy loft designed for independent work. She will even sometimes give these students her keys to access a storage area where they can complete work in almost complete seclusion. That high level of trust can be broken, though.

‘The other day,’ Anni-Mari said, ‘I saw two kids in the other classroom, and they were walking on desks, and I said, “That’s totally unacceptable!”’

The children, who had possessed her highest level of trust, pleaded their case to this veteran English teacher: ‘Well, you didn’t tell us that we couldn’t walk on desks!’

‘But I told you to do the assignment,’ Anni-Mari corrected them. ‘Do we really need to have this conversation?’

‘No,’ conceded the children.

‘You are at the lowest level of trust now,’ said Anni- Mari. ‘And next time, when we do something, whoever happens to be your partner, then they have to be in [my] room. . . . It’s a nice room, but they don’t have a choice.’

Like other Finnish teachers interviewed for this book, Anni-Mari said that trust is something that cannot be taken for granted by students and teachers. ‘You lose the trust quickly. Sometimes it takes a while to build it back, but if I see responsible behavior,’ she said, ‘then they can get to a higher level again.’

For conversation and reflection

- Think about your own education. What are your memories of teachers trusting you? What did that mean to you?

- How would you describe the relationship between trust and responsibility-taking?

- Imagine the 3 levels of trust model in your classroom.

Ideas for building trust

- At the beginning of the school year, discuss the relationship between freedom and responsibility with your students. Help them to understand that greater freedom requires more responsibility.

- Implement the three levels of trust system (see Figure 7.2) in your classroom. First, we recommend that you create the descriptions of freedom with your students. Then implement your customized version and invite feedback from the children to improve how it works.

- Tap into students’ intrinsic motivation to cultivate their responsibility. Start by studying what motivates them. We recommend that teachers begin the year by asking children to share their hopes and dreams for the school year.

- Host an independent learning week for students. Teachers and students will negotiate the work that needs to be accomplished in advance. They will also create the rules for this week together. During an independent learning week, students make progress on their own with teachers available for support.

- Teach children to check their own homework. Support them through feedback as they develop this skill over time.

- Acting responsibly requires knowing expectations. We suggest that teachers and students create class rules with one another. This practice of rulemaking encourages student ownership and reinforces the importance of shared expectations.

- Provide time for children to have unstructured time with one another in a safe environment. After a virtual lesson, consider giving students a few minutes to hang out on the call. Before offering this digital recess, students need to know the rules and agree to follow them. You can remain on the call with your microphone muted.

- As a faculty, design and run a ‘trust experiment,’ exploring what happens when students have more autonomy at school. This might include rearranging daily practices like recess, lunch, and moving through the hallways. Plan a systematic way to collect evidence, giving special attention to how students experience them being trusted by teachers and one another during this experiment.

In Teachers We Trust: The Finnish Way to World-Class Schools, by Pasi Sahlberg and Timothy D Walker, is published by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. and available now via the link.