Equality, equity and the school curriculum

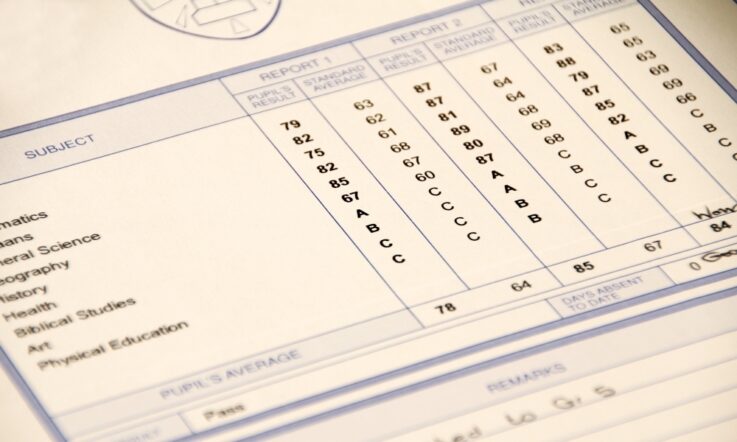

Various attempts have been made to illustrate pictorially the difference between ‘equality’ and ‘equity’. My favourite is the graphic by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation:

© 2017 Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

At first glance, providing everybody with an identical solution may seem ‘fair’, but fairness depends on meeting individual needs.

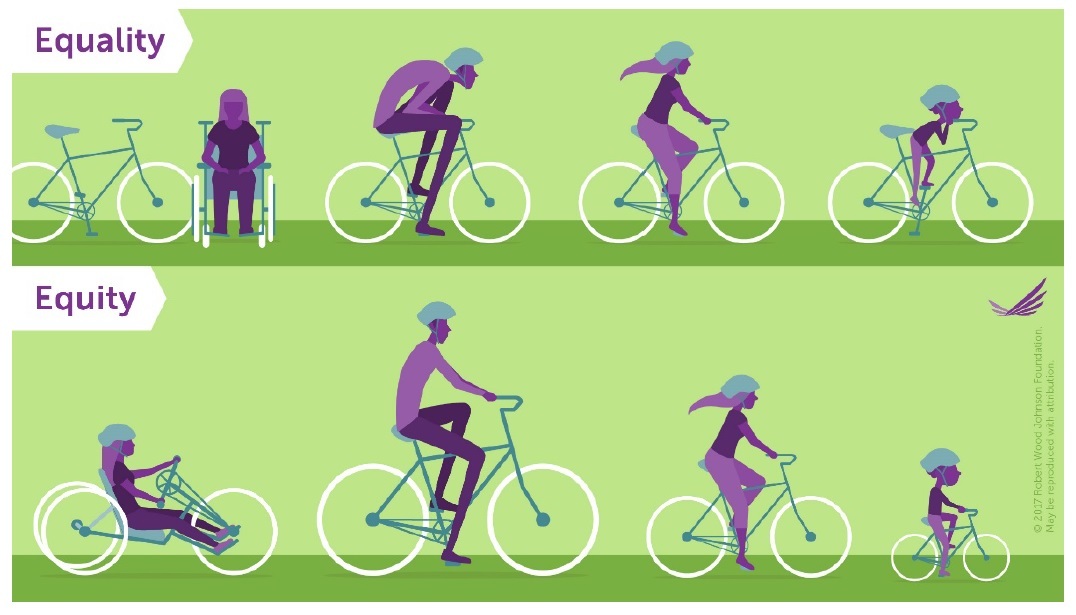

In our schools, many students can’t reach the pedals. They struggle with a year-level curriculum for which they are not yet ready because they lack the prerequisites for effective engagement. Some are a year or two from being ready for the curriculum they’ve been assigned.

As a result, they make limited progress. Each year they’re given another curriculum for which they’re not yet ready. Many fall increasingly far behind over time. Ten per cent of students are typically five to six years behind the most advanced 10 per cent of students in their year group. By Year 9, some struggling students are still back on the primary school section of the curriculum track. And students already disadvantaged by their socioeconomic background are more likely to be among those continually assigned a curriculum for which they’re not yet ready.

Other students’ knees are jammed under the handlebars. They, too, are assigned the standard year-level curriculum, but require something better suited to their more advanced learning needs if they’re to make the progress of which they are capable.

This graphic reminds me of the intention that every student should be on the same (inclusive) path of learning, and that every student should make excellent ongoing progress and eventually achieve the same high standards. The challenge is in creating the conditions to enable this. Importantly, this challenge is not the responsibility of teachers alone; the curriculum that individuals are assigned also crucially influences the progress they make.

The ‘equality’ part of the graphic reminds me that schooling is a highly standardised affair. Every student is assigned the same year-level curriculum at the same time and is given the same amount of time to work on it. All students are assessed with the same tests and examinations (administered at the same times) and their performances are evaluated against the same expectations or achievement standards. All are then simultaneously given the next year-level curriculum and the process recommences, whatever their readiness.

The ‘equity’ alternative recognises that progress is maximised when each learner is given learning opportunities appropriate to their current learning needs – well-targeted stretch challenges that may not be the same for all students. Research into human learning has made this clear. This part of the graphic also invites a more flexible approach to time. What is important is that every student makes excellent progress and eventually achieves high standards, not that they all reach the same point at the same time or even that they all progress at the same rate.

Currently, in Australia, every student is assigned the same year-level curriculum by a central curriculum authority. This standardised approach is administratively convenient and may seem superficially ‘fair’.

In my recommendations for the New South Wales curriculum, I proposed that teachers be responsible for deciding the curriculum each student is assigned, based on that student’s current level of attainment and learning needs.

To facilitate this I proposed that, for a learning area such as mathematics, a sequence of syllabuses be centrally developed. This sequence would provide the common path along which all students progress. However, students would not be required to move in lockstep from syllabus to syllabus. Instead, teachers would decide when a student had mastered the content of a syllabus and was ready to move to the next. In this way, students who required more time would have it, and students ready for a more challenging syllabus would be able to advance to it. The objective would be to maximise every student’s learning by ensuring no student was assigned a syllabus that was much too difficult or much too easy.

Obviously, this introduces a significant change in practice. Under my proposal, the decision about when a student moves to the next syllabus would be based on a teacher’s assessment of their readiness, not elapsed time. In other words, the decision would be evidence-based, not evidence-free. This is how students currently advance in music, language learning and swimming.

Some were concerned that my proposal might lead to ‘streaming’. But streaming places students on different paths, usually with different curriculum content. Some of these paths limit how far students can progress. Some lead to dead-ends. I proposed the same learning path (sequence of syllabuses) and content for every student. The only difference would be in the rates at which individuals progress through that content.

Others were concerned that teachers would not be able to manage classes in which students were not all learning the same material at the same time. Teachers I’ve spoken with disagree with this; some say they already do this. And this view of teachers as ‘deliverers’ of a centrally prescribed solution (to everybody at the same time for the same amount of time) is inconsistent with the nature of professional work. Professionals of all kinds evaluate what they’re dealing with and then provide solutions appropriate to presenting situations.

To maximise learning, teachers need to be able to provide individuals with learning activities and challenges appropriate to their current levels of attainment and learning needs. The requirement that all students be assigned the same curriculum at the same time, with the accompanying expectation that teachers ‘differentiate’ their teaching to accommodate students’ varying needs, not only can be contradictory, but also is failing to meet the needs of many students in our schools.

The answer lies in recognising that fairness and individual progress are maximised by insisting on equity rather than equality.