Getting all children off to a good start

In my recent Teacher article ‘Big five' challenges in school education I argue that one of the biggest challenges we face in improving quality and equity in our schools is to better address the learning needs of the many children who, on entry to school, are at risk of being locked into trajectories of long-term low achievement.

By Year 3, there are wide differences in children's levels of achievement in learning areas such as reading and mathematics. Some children are already well behind year-level expectations and many of these children remain behind throughout their schooling. Many are locked into trajectories of ‘underperformance' that often lead to disengagement, poor attendance and early exit from school.

Trajectories of low achievement often begin well before school. Differences by Year 3 tend to be continuations of differences apparent on entry to school when children have widely varying levels of cognitive, language, physical, social and emotional development. Some children are at risk because of developmental delays or special learning needs; some begin school at a disadvantage because of their limited mastery of English or their socioeconomically impoverished living circumstances; and some, including some Indigenous children, experience multiple forms of disadvantage.

According to the Australian Early Development Census (AEDC), 22 per cent of children starting school are ‘developmentally vulnerable' in one or more AEDC domains (physical health and wellbeing; social competence; emotional maturity; language and cognitive skills; communication skills and general knowledge).[1] On these figures, Australia has 60 000 developmentally vulnerable children in their first year of formal, full-time school. On average, these children are less likely to make successful transitions to school and are at risk of poorer long-term educational outcomes.

At the same time, children in some population groups are more at risk than others. For example, 43 per cent of Indigenous children are identified as developmentally vulnerable compared with 21 per cent of non-Indigenous children, and 28 per cent of children from low socioeconomic backgrounds are identified as developmentally vulnerable compared with only 8 per cent of children from high socioeconomic backgrounds.

A national key performance indicator (KPI)

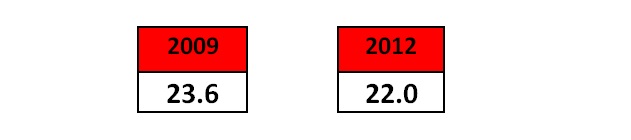

National progress in reducing the number of children who begin school at risk of ongoing low school achievement can now be monitored through the Australian Early Development Census. For example, between 2009 and 2012, the percentage of children judged to be developmentally vulnerable in one or more of the AEDC domains declined from 23.6 to 22.0 per cent.

Figure 1. Percentage of children in their first year of full-time school judged to be developmentally vulnerable in one or more AEDC domains.

At a finer level of detail, the Australian Early Development Census allows the monitoring of national progress in reducing the percentages of ‘developmentally vulnerable' children within particular population groups. The percentages for some key groups in 2012 are shown in Figure 2.

.png)

Figure 2. Percentage of children in various population groups judged to be developmentally vulnerable in one or more AEDC domains (2012).

Strategies?

The challenge of addressing the learning needs of children who begin school well behind the majority of their age group is sometimes described as the problem of children who ‘enter school not yet ready to learn'. These children are considered ‘unready' for school because of early cognitive and/or non-cognitive ‘deficits'. The implication is that more needs to be done by parents, pre-school teachers and other professionals to ensure that all children are ‘school ready'.

In reality, children are born ready to learn. They enter school ready to learn. The problem is not that some children enter school not yet ready to learn, but that some children enter school not yet ready to learn what schools are about to teach them or to function effectively in a school environment. Any ‘deficit' is a gap between where individual children are in their learning and development and the standardised curriculum and expectations of the first year of school.

Children who lag behind their age group on entry to school often become locked into trajectories of long-term low achievement. Some fall further behind with each year of school and ultimately have poorer long-term outcomes in areas such as employment, teenage pregnancy, mental health and crime.[2]

Although the traditional focus has been on ensuring that all children are ready for school, equally important is ensuring that schools are ready and able to respond to the very different stages that children have reached upon entry to school. In other words, there are twin challenges: to support and promote the progress of all children – and particularly children who lag in their development – in the preschool years; and to ensure that all children make a smooth transition into the first year of school by meeting individuals at their points of need upon entry.

Quality early childhood education and care

Children's learning and development in the preschool years are influenced by a range of factors, including relationships with parents and caregivers, cognitive stimulation, adequate nutrition, health care, and safe supportive environments. Parents' beliefs, attitudes and practices are important to healthy early child development, particularly by providing positive engagement, interaction and stimulation.

Also important is universal access to high-quality, affordable, integrated early childhood education and care, especially in the year before full-time school and for developmentally vulnerable children and children from disadvantaged backgrounds. In Australia, universal access is being facilitated through the National Partnership Agreement on Universal Access to Early Childhood Education and the quality of early childhood provision is being addressed through the National Quality Framework.[3]

Quality education and care depend on quality teaching.[4] In Australia, the Early Years Learning Framework provides broad direction to teaching and learning in the preschool years. The Framework guides curriculum decision making and assists in planning, implementing and evaluating quality in early childhood settings.[5]

Also essential are qualified early childhood educators with well-developed understandings of child development, health and safety issues. Effective pedagogy in the preschool years includes the early detection of developmental delays and the implementation of effective intervention strategies, which in turn depend on the ongoing monitoring of early learning and the tracking of children's social and emotional development.

Smooth transitions into school

An alternative to viewing early childhood education through the lens of ‘school readiness' is to recognise that, at any given age, children are at very different points in their learning and development. Rather than focusing on ‘deficits' (gaps between children's entry levels and schools' expectations), the focus during the preschool years and also in the early years of school should be on establishing where children are in their long-term learning and development and providing individualised support and learning opportunities to promote further progress.

Seamless transitions from early childhood to school often are complicated by differences in approaches, teaching styles and structures in primary schools and early childhood settings. The greater the gap, the more difficult the transition.[6] Ideally, there would be close collaboration across this transition, with educators meeting and sharing information about learning materials and activities and assessment approaches and outcomes.

Smooth transitions into school also depend on accurate assessments of where children are in their learning and development on entry to school. Baseline data of this kind are especially important for children who enter school with learning and developmental delays. Accurate assessments allow teachers to provide individualised support, including specialist support (e.g., by speech and language therapists) for children who require it. Early childhood educators and parents can make valuable contributions to the collection of information about children's learning and development at the point of transition to school.

Finally, the transition to school is facilitated by planned programs of support and targeted interventions from the moment children start school. The aim should be to ensure a seamless transition by providing optimal learning environments and ongoing close monitoring of progress, especially for children at risk of falling further behind in their learning and development.

[1] Commonwealth of Australia (2014). Australian Early Development Census: 2012 Summary Report – November 2013. Canberra: Department of Education.

[2] Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth (2007). School Readiness. ARACY: West Perth.

[3] Commonwealth of Australia (2011). Early Childhood Education and Care in Australia: A Discussion Paper prepared for the European Union-Australian Policy Dialogue, 11-15 April 2011.

[4] Elliott, A (2006). Early Childhood Education: Pathways to quality and equity for all children. Australian Education Review No. 50. Melbourne: Australian Council for Educational Research.

[5] Commonwealth of Australia (2009). Belonging, Being and Becoming: The Early Years Learning Framework for Australia. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

[6] UNICEF (2012). School Readiness: A Conceptual Framework. UNICEF: New York.